Secret Pittsburgh

Paving the Future of Coal Hill

By Joseph Pileggi

The turn of the 20th century was the beginning of a new era for the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Mount Washington. For over 100 years, the city had been both built up and destroyed by the steel industry. At the base of Mount Washington alone, within a one-mile stretch along the Monongahela River, four large iron and steel mills “belched forth dense clouds of flame and smoke” (Mount Washington Community Development Corporation) including Pittsburgh’s first successful blast furnace for making pig iron, the Clinton Rolling Mill and Furnace. While the mills had brought booming industry and thousands of workers and their families to the area, the standard of living had drastically declined. Housing quality was dwindling, scaling the Mount was treacherous, and the funiculars (inclined railroads) – the most effective connections between the residential community and the mills below – were low-capacity and expensive to maintain. Furthermore, Pittsburgh’s expansion toward the South Hills required a new mode of transportation.

In 1910, renowned city planner Frederick Law Olmstead Jr., whose father designed Central Park in New York City, made this need clear in his proposal to the Pittsburgh Civic Commission: “The inclines are expensive and of very limited capacity. The South Hills country is sparsely developed as yet, but, being comparatively free from smoke and very near to the business district, it offers unusually desirable opportunities for homes, and it must soon be thickly settled. The need for a good thoroughfare to this region will then be of far greater importance even than now.” In addition to a series of new bridges and tunnels, Olmstead Jr. proposed a “new slanting road up the hillside south of the river.” However, he worried about the feasibility of constructing the road, noting the difficulties of achieving a reasonable gradient and the high costs as “serious drawbacks” (Cridlebaugh).

Despite these potential drawbacks and many doubting experts, City Councilman and member of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers Peter J. McArdle was not going to give up hope on the roadway. After working in a rolling mill for multiple years prior to his election in 1911, the proud Mount Washington resident brought the final proposal for the roadway to the Pittsburgh City Planning Commission in 1912. Deemed the “Mount Washington Roadway,” it would be 30 feet wide, allowing automobiles to climb and descend the hill’s northern face between the soon-to-be-constructed Liberty Tunnels and Grandview Avenue. His cost estimate for the project was $416,000. Seven years later, after McArdle garnered support from the South Hills residents and the Board of Trade, a $700,000 bond issue was passed to construct the Roadway (Burton, Mount Washington Roadway). Little did he know, the project would eventually transform his blue-collar residential neighborhood into an upper-class tourist destination.

Construction (A Fictional Account of True Events)

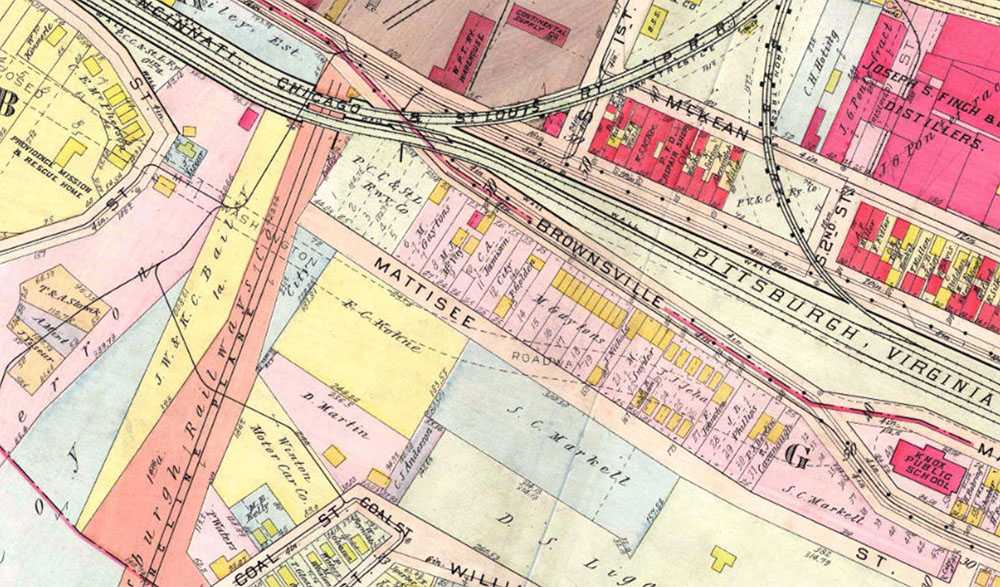

It was 1924, five years after City Councilman McArdle had funding approved for his Mount Washington Roadway, and the residents of Mattisee Street knew their time living there was short. It wasn’t a very long or populated street – there were only seven homes housing seven working-class families (mostly steelworkers) – but there were other streets marked for demolition, as well. Brownsville Road, Sycamore Street, and a section of Grandview Avenue were all in the direct path of the proposed Roadway (G.M. Hopkins Company). The Nichols family had lived at 159 Mattisee for over a decade. The father worked construction for the Farris Engineering Company while his two sons worked in the Clinton Rolling Mill less than a mile away. Meanwhile, his daughter had been attending the Knox Public School on Manor Street. Luckily, the city decided to spare her school. Nonetheless, she pleaded with her father to let her stay in her home.

At the end of the year, Mr. Nichols heard that the City of Pittsburgh was drafting his company to “drain and build supports under the Monongahela Incline” to allow the new Roadway to safely pass underneath (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette). The project was scheduled to begin early next year, and he would be a member of the crew working on it. Ironically, this meant he would help build the road that would soon uproot him and his family from Mt. Washington.

Even though Mr. Nichols understood what was at stake and he sympathized for his family, his job was his livelihood and he knew the construction of the Roadway was inevitable. For residents living on top of Mount Washington, scaling the steep cliff was extremely treacherous and the inclines were no longer suitable. Most of his neighbors recognized this as well, except for G.E. Johnson down the street, who was wrestling with the city to keep his property at 167 Mattisee.

Over a year later, a chilly December day in 1926, Mr. Nichols’ was working with four of his coworkers under the Monongahela Incline. He had been digging for several weeks along the 200-foot cliff, as his clothes had become tattered and his energy low. The dirt on his face concealed his cheeks, rosy and numb from the icy air, just as the smog in the air concealed the buildings Downtown and the Panhandle Bridge. The Farris Engineering Company was not the only crew excavating for the Roadway project. Vang Construction Company was contracted for the upper half from Grandview Avenue to the Castle Shannon Incline, and the Booth & Flynn Company for the lower half from Castle Shannon to the newly completed Liberty Tunnels (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette).

Mr. Nichols had moved his family out of their home a few months before construction. The project was delayed after the cost of the Roadway had unexpectedly grown to $1,250,000 at the start of construction, $550,000 more than the bonds issued in 1919, which allowed the family a little extra time to relocate itself (Burton, Mount Washington Roadway). As for Mr. Johnson down the street, his house was the only one on Mattisee Street spared after Roadway construction diverted slightly south. Regardless, he would soon move out of his home, too.

Completion

Exactly four years after construction began and with over $1,000,000 invested, the Mount Washington Roadway was finally paved. Councilman McArdle succeeded in sparking a new era of urban transportation in Pittsburgh and officially dedicated the Roadway at a ribbon-cutting ceremony on July 17, 1928. Yet, there were still inklings of the past haunting the hillside.

Due to the razing of communities and the “fumes and byproducts of industrialization” that “had poisoned the flora,” the hillside was nearly bare. To breathe life into the hillside, the City Planning Commission adopted a “Mount Washington Beautification Plan” to plant 8,000 trees on the north face of the hill in one year. Unfortunately, when the Great Depression hit shortly after, only $25,000 of the $75,000 in funding was appropriated, and the plan stalled (Burton, Short History of the Evolution of Coal Hill).

Fast-forward to the decades after the Depression and Pittsburgh’s steel industry was disappearing quickly. Councilman McArdle passed away in January 1940 while in office, and the Mount Washington Roadway was renamed P.J. McArdle Roadway in his honor. The Clinton Rolling Mill and Furnace closed in 1928 and was eventually replaced by modern-day Station Square (Rivers of Steel).

Once a blue-collar community with low-quality housing where someone may have raised a family or retired at the end of a long day in the steel mills, Mount Washington transformed into an upper-class community full of multi-million dollar condominiums, tourists, and first-class restaurants. By increasing accessibility, the McArdle Roadway was at the center of this transformation. Self-described urbanist Edward Soja would call it a “reflective mirror of societal modernization” or a “fully lived space.” The construction of the road, a physical alteration of Mount Washington, had changed both the neighborhood’s significance and the way people interacted with it.

Similarly, one may also view the construction of the Mount Washington Roadway as a small but important step in Pittsburgh’s gentrification of low-income communities. In Charlee Brodsky, Jim Daniels, and Jane McCafferty’s book From Milltown to Malltown, photographs and poems explore the erasure of the working-class past in Homestead with the construction of the Waterfront Mall. Likewise, while the McArdle Roadway and subsequent development of Grandview Avenue made Mount Washington one of the most famous places in Pittsburgh, they also pushed low-income residents to the area’s fringes.

It can be difficult to find evidence of the past in Mount Washington aside from the Monongahela and Duquesne Inclines, but just as in Homestead, “every inch of this geography contains a blistered history” (McCafferty). Viewing archival photos and hearing stories of the past, one can imagine what used to be where the Roadway, restaurants, and overlook platforms stand now, and furthermore, how that history has made the area what it is today.

Works Cited

Burton, Clint. Mount Washington Roadway. 2 May 2015. The Brookline Connection. Short History of the Evolution of Coal Hill. 2 May 2015. The Brookline Connection.

Cridlebaugh, Bruce S. Lower P.J. McArdle Roadway. 14 May 2003.

G.M. Hopkins Company. Pittsburgh Historic Maps. 1923.

McCafferty, Jane. "On This Very Spot." Brodsky, Charlee. From Milltown To Malltown. Gross Pointe Farms: Marick Press, 2010. 57.

Mount Washington Community Development Corporation. MWCDC.org. 31 March 2005.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. "Mount Washington Roadwork Halted Pending Approval." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 26 September 1925: 9.

Rivers of Steel. Steel Footprints: A Virual Tour of the Pittsburgh Industrial District. 2017.

Soja, Edward W. Thirdspace. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1996.