Secret Pittsburgh

Properties of Space

By Alexander Leighton

“Make yourself at home, now. You’ll stay here a while…” - Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist

Out of all the buildings in the world, why on earth visit a prison? If you’re lucky enough to have a day off work, why not visit somewhere more jovial instead? Or go to a more that takes you a galaxy far away from the trivialities of modern life.

Well, perhaps such escapism ultimately does more harm than good. I think my generation often feels underwhelmed by archaic sites; technology has progressed to such an insane degree, and cutting-edge architecture increasingly resembles the Jetsons, so its hard to really scale our expectations back to the stone-n’-grit of the past. Sadly, the sophisticated structures of the Romantic era can feel like chalk drawings on a wall next to the wonders we’ve become accustomed to. But relics of the past hold the important task of illuminating just how far we’ve come.

Downtown Pittsburgh, today, is most commonly associated with grandiose buildings of glass and steel. The skyscrapers on the long stretch of Forbes Avenue generate profit, but the sleek structures seem too impersonal, too slippery, for any substantial human story to be attached to them. Not so with the Allegheny Courthouse. Clocktowers, fountains, spires… the complex looks like something ripped straight from a fairytale. These walls contain a history, but not the happily-ever-afters we commonly associate with such gorgeous architecture. After all, it’s home to “The Bridge of Sighs”. Lives have been sentenced and rotted away here: even today, it is regarded as a judiciary building first and foremost, a punishing ground for those deemed guilty. That particular identity is in the past, but hangs over the way we perceive the courthouse. To many both living and dead, this is a place of doom, their memories of it tinged with regretful, claustrophobic longings for escape.

And yet my first encounter with this building was mostly dominated by feelings of awe. When visiting, it was the beginning of fall, with tumbling leaves and charged sense of change in the atmosphere. But the sky was clear, and the sight of familiar skyscrapers was offset by a castle whose walls possessed more windows than bricks. I entered the courtyard, greeted by the sight of a fountain with water of the bluest blue. I took pictures, an act which seemed almost sacrilegious within such a space: this was a timeless place, in which rudimentary photography and blinking screens appeared to have no belonging. Soon, of course, these feelings would be replaced and confirmed by the law, as no recordings are allowed of the building’s interior. But by then, I was too busy basking in the sights of grandiose staircases, painstakingly painted mosaics, and crystalline chandeliers to miss my phone.

Why was I so romanticized by this place? Such a feeling was almost a contradiction in the face of the knowledge of the courthouse’s relation to the prison next door. And the heavy surveillance should have made me feel awkward, self-conscious, even restrained. As Foucault would describe it, there was an “anonymous power” just out of periphery. Even as an innocent man, I felt its influence. To the prisoners, it must have been overwhelming. I pushed these thoughts out of my mind, just trying to enjoy the tour. This empathy would only distract me from the gorgeous majesty I was within. Everyone spoke to me in welcoming, warm tones. The staff was so polite. As an innocent man, why would the judicial power surrounding me have any effect?

Properties of Space

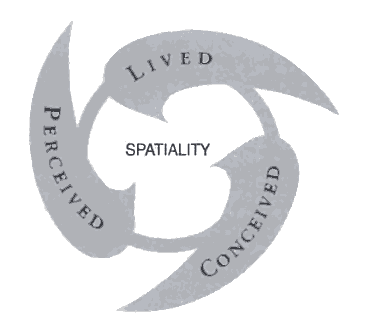

My initial thoughts while within the courthouse were so conflicting, so contradictory… but it ultimately makes sense. According to Space Theorist Edward Soja, ‘sacred’ spaces can be divided into three categories, each building upon, and complimenting, one another into a unified experience. These “Trialectics of Spatiality” each deal with specific influences on our viewings of a site: we see the room’s physical traits (perceived) and regard it with adoration, disgust, or some emotion in-between (conceived) while knowing that this area has had an impact on the people who came before (lived). These aspects of space in turn feed back into our own “Trialectics of Being”, the historical, social, and spatial aspects that define who we are. The differences between these two cycles, and the components within them, are only imagined. Remove one, and the fragile house of cards comes tumbling down.

Now, it’s weird to consider a prison ‘sacred’, but I think this type of division can also be neatly applied to the courthouse, and may explain why I had felt such contrasting emotions upon visiting the site. The site had an impact on me both real and imaged, from the moment I entered. We rely on perception first and arguably foremost, and the sight of the Courtyard is certainly overwhelming. The spired buildings and the monolithic clock-tower are physically imposing, while the open design of the courtyard works as both a conduit for light and a grand expanse of space. This all tied in with my conception of the area: it looks like a fairy-tale castle, and its remove from our everyday reality is only enhanced by its placement next to sky high steel structures. If this building were to be totally removed from the history that came before it, we’d almost view it in a romantic light. It’s simply a beautiful design… but one that’s housed criminals.

But the lived-in space of the courthouse fundamentally impacted my encounter, and emotional reaction to, the building. For most of my viewing, this history was in the background, an abstract that was somewhat easier to ignore. That separation vanished upon leaving the courthouse and entering the prison.

Bringing it all Together

The prison, aside from the metal detectors visitors must walk through, conveys a surprising feeling of openness. You’re presented with a giant glass wall, flanked by Romanesque pillars, covering four stories. It looks like another building entirely. However, after seeing what is to come, the grid-like structure of the windowpanes begin to resemble bars. But in this initial moment, my feelings of awe from the courthouse were retained.

But then we walked to the display created to represent what the prison complex once looked like. And at that moment, it fully struck me for the first time: this is a prison. Such a statement is obvious, of course, but there is a difference between knowing something, and experiencing it first hand. We’ve seen representations of prisons in visual media so often that they’ve become almost second-nature. And every television show or film featuring a prison ultimately ends with someone escaping it. Such portrayals trivialize what the physical reality truly is: this place is suffocating, small, and without escape. We know prisons are made of bars, but is only upon seeing the steel firsthand that we realize how effective they are at containing convicted men and women.

At once, everything changed. The feelings I had were no longer in the abstract; everything, from the grandiose architecture to the buildings within them, lead to this area. It was the heart that gave the complex purpose. It seemed to small to contain lifetimes, yet that was in fact it’s very cause. Before visiting the site, I had read excerpts from Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist, and found the thoughts of a jailed man to be sad, compelling. But it was only upon entering this space that I truly achieved the empathy I had tried to block from my mind. Without doubt, it impacted the way I would look at the courthouse in the future: no longer would it be just a gothic masterpiece to me. I understood why it would be such a fearsome site for so many, as the natural light seeping through the open courthouse served to give way to the isolation within these cells.

Back to the Digital

I imagine that my next dozen or so encounters with a prison will be through the safety-net of phone and video screens. But I still remember how claustrophobic it was to be within that space. And that is why I think it’s so important for people to visit this site. The architecture is beautiful, but ultimately a facade: the true impact lies in the cold and lightless steel cells found after crossing the bridge of sighs.

The impact the cells had on me were not only retroactive, however, as it will also affect the way I view prison stories moving forward. Every time I see a man within a cell, it will be that much more devastating: I don’t know how it feels to spend a lifetime behind bars, but I now know what the view through them looks like. I have never been so thankful to leave a building, or feel cooling fall air blow through my hair. It might not be an altogether enjoyable experience to visit a prison, but is perhaps a necessary one

Works Cited

Berkman, Alexander. Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist. New York: Schocken, 1970. Print.

Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Lost Angeles and Ither Real-and-Imagined Places. Cambridge MA: Blackwell Publishing Inc., 1996.