Secret Pittsburgh

More than an Inspiration

By Christopher Fisher

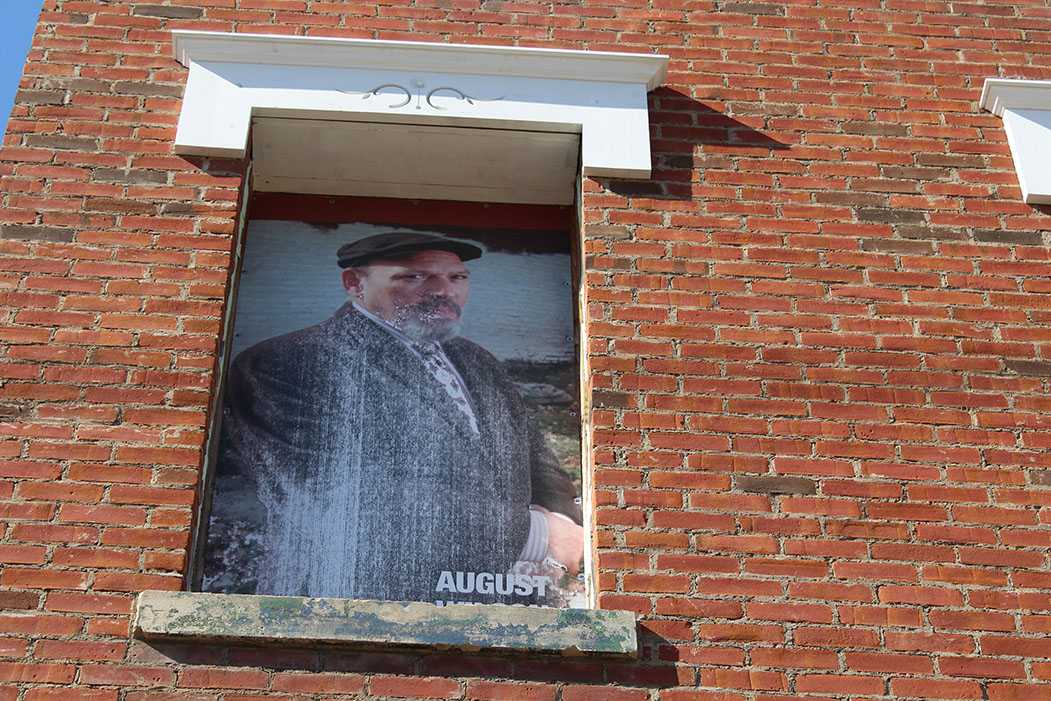

August Wilson is an inspiration for most, if not all, of the African American community, especially those in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. Growing up with a lot stacked against him, Wilson was able to persevere and make his way on to the big stage through his works in theatre and in the communities he was a part of. He would go on to use his power and stardom to reach out to African Americans with all interests, although he was more focused on giving those interested in the arts a voice. Wilson was able to accomplish such victories through his education and his faith in his childhood in the Hill District. The route Wilson took allows his legacy to give the community that made him what he has always wanted them to have; a voice.

Wilson was a very intelligent person from an early age. It is known that his mother Daisy Wilson taught him to read when he was just four years old (Glasco & Rawson 7). August called the ability to read a transforming point saying, “[You can unlock information and you’re better able to understand the forces that are oppressing you]” (Glasco & Rawson 7). With how fueled Wilson was in his adult years to create equal opportunities for his African American counterparts this was a very important milestone for him. He went to six different schools growing up before getting tired of the bigotry and finding his own way. In the beginning he had to switch schools due to relocation, but once Wilson made it to high school he just had enough. The last straw for him was when he attended Gladstone High School in Hazelwood. Upon joining the after-school college club he felt it necessary to prove his worth and submitted a twenty-page research paper on Napoleon. Wilson received an “F” for plagiarism since his teacher believed one of his older sisters had written it. He barely fought the teacher and was so insulted he threw the paper in the wastebasket on his way out of the classroom never to return again. Discussing this story in an interview Wilson said, “[I dropped out of school but I didn’t drop out of life]” (Glasco & Rawson 9). He was not giving up on education, because it was something he wanted and loved so deeply. He just felt that the system was against him and realized he had to do it on his own. From that point on, Wilson would leave the house each morning and go to the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in Oakland. This was his real school. Wilson stated, “[…they had all the books in the world. …I felt suddenly liberated from the constraints of a pre-arranged curriculum that labored through one book in eight months]” (Glasco & Rawson 9). He was finally at peace with his education and he did it on his own.

Wilson would go to use his self-achieved education for great things. Accumulating many awards and accreditation for his plays, he never forgot about his roots in the Hill. It was the Hill District which he set nine of his ten plays in. He made a claim that its homes, offices, shops, streets, and dusty backyards are all fertile ground (Glasco & Rawson 4). Although his plays were being performed around the nation, the Hill in his memory is where, “…he kept dipping the ladle of his art” (Glasco & Rawson 3). Wilson has made a very clear emphasis that although he left for a period of time the Hill lives on in his imagination. He would not have kept coming back and revisiting his memories through his plays if it did not. Wilson acknowledges the poverty and hardships he faced in the Hill growing up, but nevertheless remained firm on the idea that he had a wonderful childhood (Glasco & Rawson 7). The Hill made him who he was and that speaks volumes to others facing similar situations. It does not surprise me that his next project was to speak out and help inspire others to follow in his footsteps.

As a self-made and good-hearted man, August Wilson was able to help the people who at one point helped him. He rose to high ranks in the arts community and, whether or not he wanted it, he was given a voice that could be heard over everyone else’s. Wilson spoke out about getting African American people in the arts community equal chances and in the end decided to take a different approach. As he did with his own education, Wilson, while speaking to the 11th biennial Theatre Communications Group National Conference at Princeton University, he challenged African American arts students to find their own way in (Wilson 43). He acknowledges the discrimination they face, but also assures them that, “Theatre asserts that all of human life is universal. Love, Honor, Duty, Betrayal belong and pertain to every culture and every race” (Wilson 35). Wilson says the only way to gain the access and respect they deserve is to take it but take it together.

As you recount his life and all his achievements, August Wilson is more than an inspiration. When he was not getting treated fairly and the same opportunities as everyone else he did what he had to ensure his success. He practically taught himself and shot himself up through the arts community to the top becoming one of the best playwrights of all time. It would have been very easy to never look back and move on from the place where he experienced so much strife, but that was just unfathomable to him. That house he grew up in on Bedford Avenue in the Hill District was always in the back of his mind and it was that house he always came back to in his head to give him the inspiration he needed to move forward. Wilson earned a voice for himself and for African Americans in the arts community. He used that to the best efforts he could, speaking at conferences and to students to challenge the dominant ideology in theatre and encourage young African Americans in the arts community to take what they deserve. August Wilson will forever be indebted to by them and it was the path he paved from his childhood in the Hill District which is going to keep pushing the culture he grew up loving moving on through theatre.

Works Cited

Glasco, Laurence A., and Christopher Rawson. August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays. Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2011.

Wilson, August. The Ground on Which I Stand. Nick Hern Books, 2001.