Secret Pittsburgh

August Wilson: From Bedford Avenue to Broadway

By Lauren Myers, Kelsey Shuck, Mazin Al-Ghanami, and Zoya Arebamen

This page contains the transcript, show notes, and sources for the fourth episode of the Secret Pittsburgh Podcast, Season One . To listen to the episode, as well as the rest in the series, visit our SoundCloud.

Transcript

Zoya: Hello! Welcome to Secret Pittsburgh! In the past 15 weeks, we’ve traveled across the city, learning the stories of Pittsburgh’s people and places. I’m Zoya and in this episode, “August Wilson: From Bedford Avenue to Broadway,” we will explore the story of the famous playwright August Wilson.

August Wilson was an American playwright known for his influence on theater that has resonated across generations. Honored with two Pulitzer Prizes for Drama, his groundbreaking contributions not only earned him a place in theater history but also worldwide admiration and acclaim. Born on April 27, 1945 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he was the fourth child of six children. His mother, Daisy Wilson, worked as a cleaning woman, while his father, a German baker, remained estranged from the family, offering little to no emotional or financial support. He was raised instead by his step-father, David Bedford.

Our class took a tour of the August Wilson House with Dr. Ervin Dyer, allowing us to see what it was like for Wilson as a child of a poor family in the Hill District.

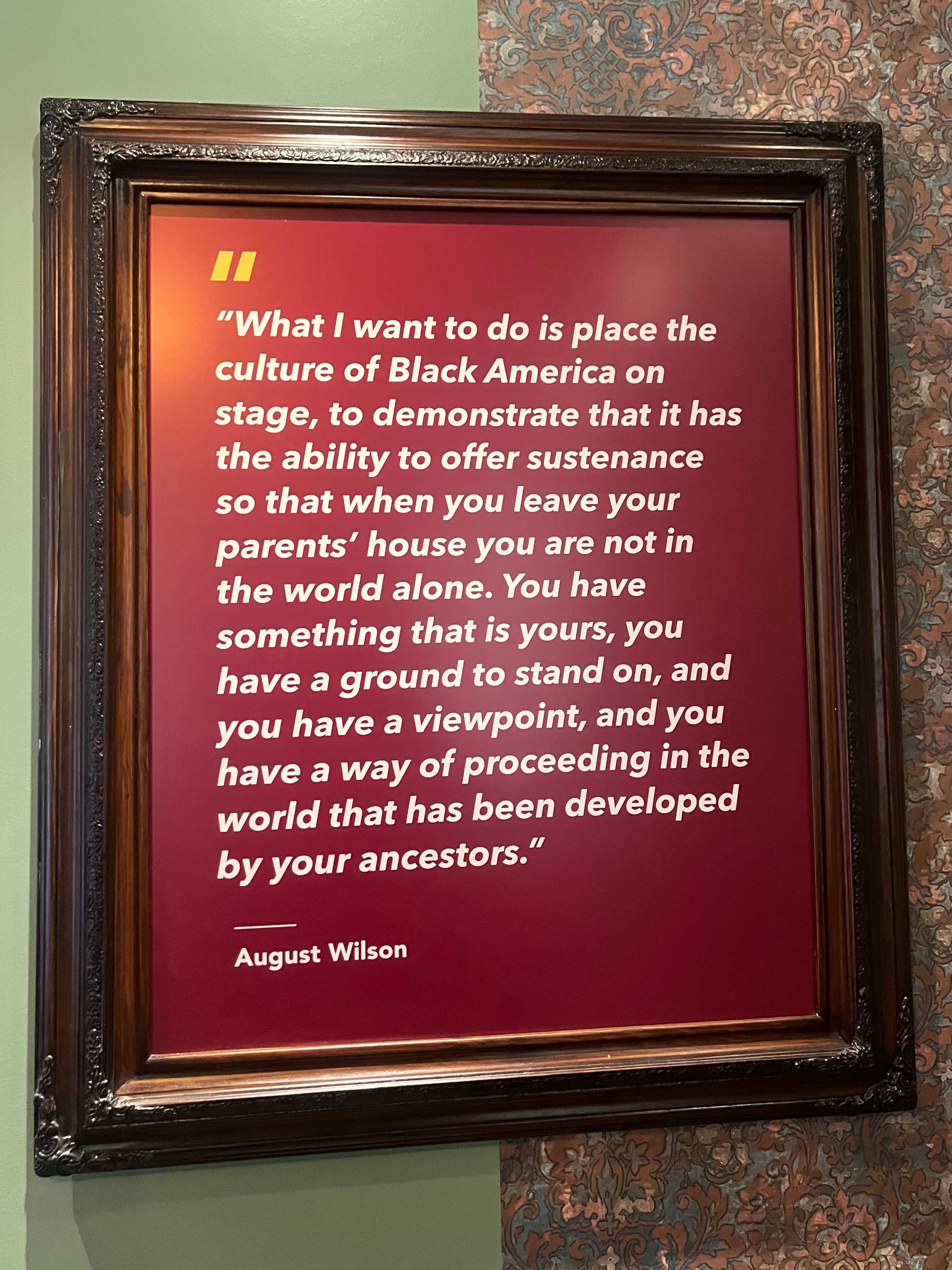

Dr. Dyer: Yes so, the family lived here in two rooms. Wilson and his five other siblings lived here. They slept in this room. They would sleep on pallets in the night and roll them up and put them in a corner during the day. This became a living space. The family struggled economically. Hence living in the rear of the building, it would have been cheaper to live here. And also at the time that he lived here, the house was quite dilapidated. There’s a story that Mr. Wilson had a high school friend who lived in the upper part of the hill, known as Sugar Top, which was for more middle class and wealthy families. And the friend told his mother, I’m going down to visit Wilson, my friend August. And his mother said, no I don’t want you to go there, because I don’t like that part of town. And the story goes that when he got here, he was so traumatized by the condition of the house that he left. And so while the home is restored and you see it in a pristine condition today, it’s important to know that when Mr. Wilson grew up here, it was a different experience because of the family’s struggle with economics and finances. Nevertheless, Mr. Wilson believed in such a thing as sort of cultural wealth and spiritual wealth, right? And he considered this to be a sacred space for him because he was introduced to the concepts of sacred, spiritual, and cultural wealth in this house. Through the stories his mother told him about how she persevered, about how her family persevered, about the people in the community and their struggles with oppression against racism and other obstacles. And so he felt a lot of pride in that. And he felt like those stories that she gave him gave him the spirit and the strength and he wanted to share those stories through this place. So the people that you see in this place are reflecting of the people that he felt their stories should be told. So he’s having to give them voice. And so he got that right here in these two rooms.

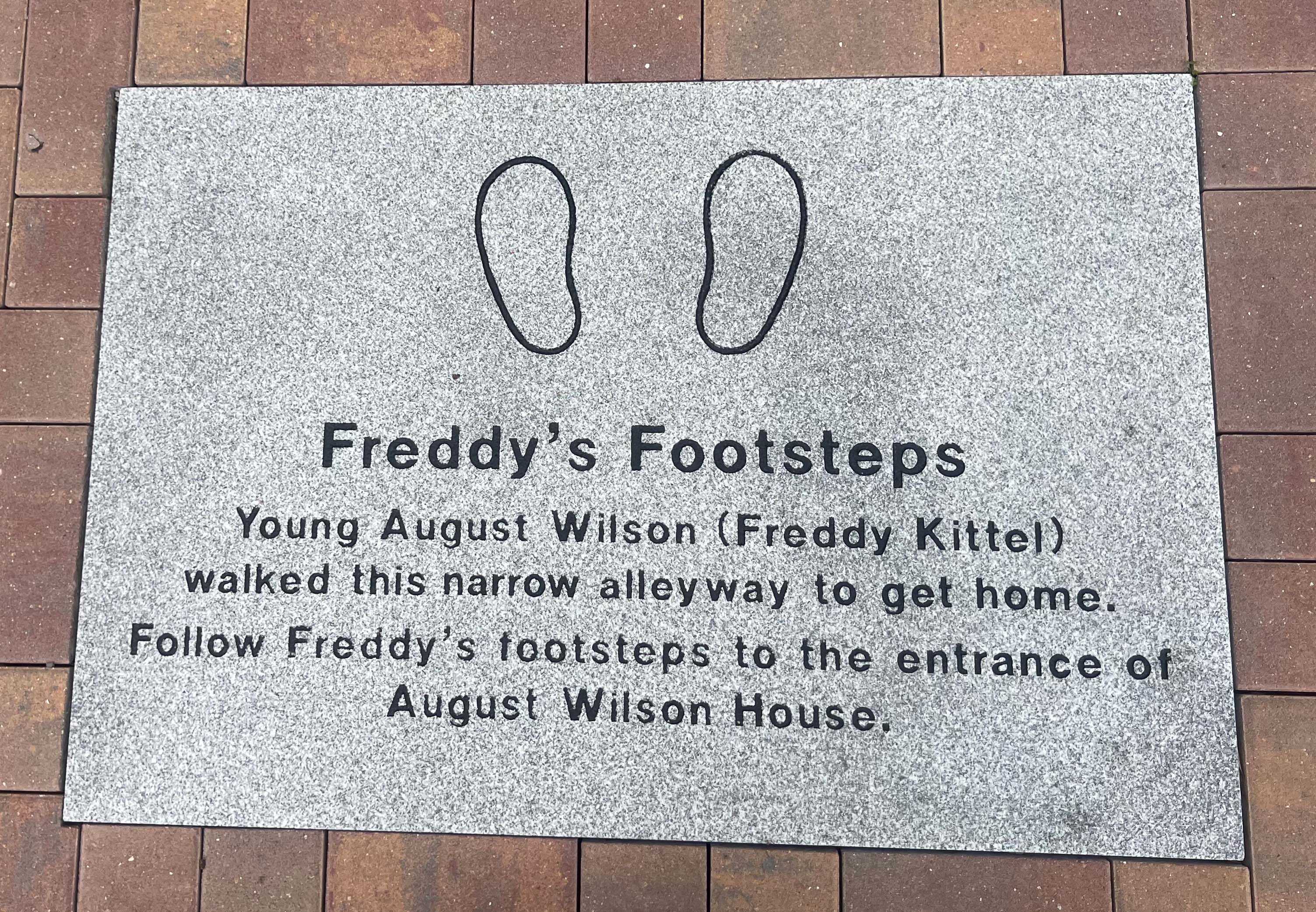

Zoya: Wilson spent the first 13 years of his life living at 1727 Bedford Avenue in the heart of the Hill District of Pittsburgh. It was a two bedroom home he shared with his five siblings and mother. A Jewish family managed a mom-and-pop store in the front, while two Italian brothers repaired shoes and watches next door. August Wilson came of age within a community that intertwined the stories of Jewish, Italian, and Black residents. However, the landscape of the Hill District transformed post-1968, evolving into a predominantly Black neighborhood.

Given August Wilson’s contribution to the Hill District and his childhood home, it seemed essential for us to explore the history and its promising future. We had the privilege of speaking with Dr. Ervin Dyer, an acclaimed news journalist and storyteller known for his coverage of African American life and culture. Dr. Dyer collaborates with the August Wilson

House as a board member to foster a deeper connection to Wilson’s legacy and purpose in the community. Given his expertise, Dr. Ervin Dyer was able to give us a brief history of the Bedford home, originally a farmhouse built in the 1800s, and the reconstruction that took place spanning over a decade.

Dr. Dyer: When it was built, that area of the Hill district was very rural, and it was considered like farm land. So it was a farmhouse. And then there were additions made to the house as the Hill community began to develop, and immigrants poured in from the American South and from communities overseas. The Hill grew and became very crowded. So the additions were made to the house to create living spaces for people. So it became a store and then it rented out space for people to live in. But August Wilson lived in the house in the 1940s, the mid 1940s. The property had become very dilapidated. I remember living in the Hill and walking past August Wilson’s house and seeing it be dilapidated and thinking to myself how wonderful it would be to have this structure redeveloped as part of Mr. Wilson’s legacy, because I knew who he was and I knew that this was his home. Although many people in the community had no idea that this house that was falling down belonged to him. And I lived in the Hill. I remembered walking past his house when it was falling down, wishing, thinking, hoping that one day it would come back and now it’s back. And I’m a part of the work of putting his legacy out into the community. It’s just a phenomenal sense to have seen that happen.

Zoya: It was within those walls of 1727 Bedford Avenue, where Wilson was shaped by the resilience of his family and his mother’s teachings. It was within his community, where he drew inspiration. It was also there where Wilson faced discrimination and challenges. August Wilson’s life took a turn in 1960 when, facing false accusations of plagiarism, he dropped out of high school. Undeterred, he assumed control of his education, at the Pittsburgh Public Library. Dr. Dyer gave our class a tour of the August Wilson House and shared this story.

Dr. Dyer: He started much of his early education in Catholic school, because his mother was domestic with the church, right? And she could get tuition for her kids that was less expensive than what others had to pay, and some of it was free. So she sent her kids to Catholic school, but Mr. Wilson hated that experience. He was an outsider, for a lot of reasons, because he was mixed race. And because of his economic situation, he found it difficult finding out where he fit in. He did well in school, but he didn’t really like it.

Zoya: Although he did not enjoy highschool, it’s undeniable that August Wilson was a fantastic writer, even in 9th grade.

Dr. Dyer: So yeah, he wrote a paper on Napoleon and the paper was so good, the teacher thought he had plagiarized it. And Mr. Wilson, being a teenager, and being sort of, finding that indignant to think that someone would think that he would cheat and plagiarize a paper, dropped out of school. He was in the ninth grade. So, what he would do, initially, is he would go back to the school every morning to the basketball court and play basketball, hoping that one of the teachers would ask him to come back into the building and restart school. They never did. And because his mother was such a stickler for education, he could not come back home. So he went to the library and began to educate himself in the Carnegie Library, where he read books. And he read books. And he read books. And he read books. And Mr. Wilson graduated from the Carnegie Public Library.

Zoya: During the late 60s Wilson pursued his artistic interests with the formation of Pittsburgh’s Centre Avenue Poets Theatre Workshop and co-founded the Black Horizon Theatre Company, a volunteer troupe. In 1973, he wrote the play Recycle, drawing on the personal experiences of a troubled marriage. Dr. Dyer shared with our class how poetry influenced his writing and plays as well.

Dr. Dyer: His first identification as a writer was as a poet. He wrote a lot about his family, his failed romances. And sometimes it was very obtuse and thick, right? In 1969 at the University of Pittsburgh, there was a group formed called the Black Action Society. And one of the things they created was a newsletter. And they had some contributions from August Wilson. And the editor told me this story that they read his work, and it was so dark and so thick and so heavy, they didn’t quite know what to do with it and they pondered whether to use it. They eventually decided to use one piece—and for their benefit, now their collection of newsletters has this original August Wilson poetry as part of their archive. But I went back and read it, and it takes you a while to read. He was influenced by the Black Power Movement, the Black Arts Movement, and so he wanted poetry to express those views and to reflect those views. And um, yeah, it could be very thick sometimes. But he did write about his romances, mostly they failed. He was a lovesick poet. But a lot of writers talk about his poetic influence showing up in how he constructs dialogue in his plays. And so the structure did not go to waste. He found a way to use it.

Zoya: The turning point in Wilson’s career arrived in 1982 when an early draft of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” was accepted for production at the O’Neill Workshop. This marked the end of his anonymity, thanks in part to the guidance of Lloyd Richards, an actor and director who became Wilson’s mentor. Thus began the rise of a playwright whose work would profoundly impact American theater and culture.

The more he wrote, the more people had to say regarding his work. August Wilson faced criticism for both his topics and themes, as well as his defiance against the established norms of white American dramas. People believed no more could be done in regards to racial equality. In a review of Wilson’s play, Robert Brustein stated that his storylines were, “monotonous, limited, and locked in a perception of victimization.” This criticism indirectly states that Wilson’s focus on African-American experience was narrowing the scope of his work. Wilson advocated for increased visibility of Black playwrights. He was against the system that predominantly showcased plays deemed worthy by white audiences. He emphasized the need for a broader and more inclusive recognition of diverse narratives within the African-American community. He disapproved of the practice of Black actors taking on traditionally white roles, arguing that the African American’s voices were rarely heard on stage.

In Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, August Wilson showcased his perspectives on fame concerning African Americans. In regards to the work that attracted white audiences and the often insincere appreciation that accompanied it. This work not only ironically marked the beginning of his success in the industry but also set the stage for these themes throughout his Century Cycle of plays.

In the play, Ma Rainey, an up and coming musician, navigates the challenges of the music industry in the 1920s. Conflict arises as the band members hold conflicting views on the interpretation of the blues, coupled with concerns about exploitation from white producers and the management of the recording studio. In the words of Wilson’s sister, “How does a Black man become a successful American without sacrificing his real culture and the richness of his identity?”

In the play, Ma Rainey conveys that her worth to the producers is reduced to her voice, and she feels used by those in control. She feels as if she’s being treated like a commodity. “They don’t care about me. All they want is my voice,” Ma Rainey says. “They ain’t got what they wanted yet. As soon as they get my voice down on them recording machines, then it’s just like I be some whore and they roll over and put their pants on. Ain’t got no use for me then. I know what I’m talking about. You watch.”

Following the idea behind Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, August Wilson decided to develop the Century Cycle, also known as The Pittsburgh Cycle: a collection of ten plays about the African American experience. Each play stands alone as an independent work yet they are all connected. Wilson’s strategy of composing a play for each decade of the 20th century serves as a deliberate narrative device, highlighting a long journey with little to no progress.

A notable play from the cycle is Two Trains Running, which takes place in Pittsburgh in 1969. Two Trains Running revolves around the theme of capitalism, and the connection among hard work, rightful compensation, fate, luck, and identity. A clear example of rightful compensation is shown through the character Hambone. He paints a fence and his employer, Lutz, states that if he paints it well, then he will get a ham. Hambone paints the fence perfectly. It even stands the test of time, since he was asking for a ham for nearly a decade. This interaction symbolizes broken promises and the exploitation of African Americans by white society. This story resonates with real-life instances, as shared by Dr. Dyer as he recounts a similar situation in Wilson’s mother’s life.

Dr. Dyer: She was a person herself of high moral character. She listened to the radio, and one day on the radio, she won a washing machine. When she went to go retrieve the washing machine, because she was an African American woman, the gentleman tried to give her a second hand machine. She did not take it. So, she had six children, and she refused a washing machine because she was not going to take anybody’s second hand goods. She felt that was beneath her dignity and she was not being treated as an equal. So the strength of her character was something that she passed on to Mr. Wilson through how she lived and the stories she told. Everything he learned about the value of culture as being foundational to people understanding who they were was learned at this kitchen table with his mother.

Zoya: Wilson himself stated that the play revolves around two fundamental ideas: cultural assimilation and cultural separation. These were the two trains running. He wanted to portray a character that neither of these paths proved useful. Instead, the character had to construct a new path—a metaphorical railroad—to reach their destination. This narrative draws inspiration from Wilson’s own upbringing, reflecting the transformations he witnessed in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, where the sense of community was disrupted by the appearance of progress.

As this episode comes to an end we encourage you to check out our second episode, “The Hill’s Hidden Histories and Lasting Legacies,” where we will delve into the history of the Hill District, the effect it had on Wilson’s life, and the August Wilson House as it is today.

Thank you for joining us as we uncovered one story of the August Wilson House and his legacy. We hope you are inspired to visit this place and to find your own Pittsburgh stories. Please tune-in to all the episodes we’ve produced this season. You can find show notes and a transcript at secretpittsburgh.org. This episode was hosted and written by me, Zoya Arebamen, and my group members Mazin Al Ghanami and Lauren Myers who served as the audio editors, and Kelsey Shuck who also wrote and researched this episode. Thanks for listening!

Show Notes

If you are interested in learning more about the August Wilson House, you can check out their website, and schedule a visit or attend an upcoming event.

To supplement the information given in the podcast, you can also visit the Secret Pittsburgh website and learn more about the Hill District, the August Wilson House, and other locations in Pittsburgh!

Bibliography

August Wilson House, http://augustwilsonhouse.org.

“August Wilson: The Ground on Which I Stand ~ August Wilson's 10-Play Cycle: Scenes and Synopses.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 23 Dec. 2020, https://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/august-wilson-the-ground-on-which-i-stand-scenes-and-synposes-of-august-wilsons-10-play-cycle/3701/.

Bill Moyers, “August Wilson’s America: A Conversation with Bill Moyers,” American Theatre 7.6 (1989): 14.

Bogumil, Mary L. Understanding August Wilson. The University of South Carolina Press, 2011.

Dial, Thomas. Personal Interview. 3rd November 2023.

Dyer, Ervin. Personal Interview. 7th November 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/-CASK-/sounds/623288/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/-CASK-/sounds/623286/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/camel7695/sounds/577085/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/camel7695/sounds/577085/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/Migfus20/sounds/559850/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/leytos/sounds/251000/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

“Find Any Sound You Like.” Freesound, https://freesound.org/people/Danskin54/sounds/344624/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2023.

The Hill District (Pittsburgh, PA), a story, https://aaregistry.org/story/the-hill-district-pittsburgh/.

Zach Cene, “August Wilson House,” Hill District Digital History, accessed October 26, 2023, https://hillhistory.org/items/show/15.