Secret Pittsburgh

At the Corner of Freedom and Fighting

By Samantha Temples

Picture this: It’s 1968. You’re watching the houses a block down go up in flames. The same houses your community fought so hard to keep for the residents in the Hill. The houses your barber and post-man have lived in since they were born. The houses the city tried to take away from you and your neighbors. You could stop the city from building further up the Hill, but you can’t stop the fire from burning it all to the ground.

“Don't you try and go through life worrying about if somebody like you or not. You best be making sure they doing right by you.” – August Wilson, Fences

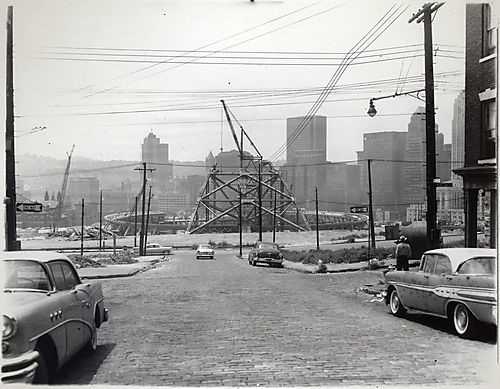

At first, Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority had good intentions in building the Civic Arena—or so we hope. The agency wanted to utilize urban renewal to save the city from decay and deter people from leaving Pittsburgh, both problems affecting Pittsburgh tremendously in the 1950s. The URA imagined a more beautiful downtown, showcasing a magnificent stadium meant for theatre and sport. After much debate, the location for the famous Civic Arena was settled upon: the Lower Hill—right on top of the homes of about 8,000 people (old.post-gazette.com).

The URA began its demolition of the Lower Hill in 1956. At the time, the Hill District was an eclectic space for small businesses, bars, gambling, prostitution, jazz, movie-theatres, restaurants, markets, and much more. While the Hill may have been exciting and lively, the neighborhood also had its fair share of problems: poverty, dilapidated infrastructure, sickness, and difficulties with sanitation (Glasco 25-26). These were the issues the URA capitalized upon. They used these problems to confirm why the Lower Hill needed redevelopment. The Hill’s prominent leaders saw the potential in a redeveloped neighborhood, leading them to make a deal with the devil: they agreed to let the Civic Arena be built upon the debilitated Lower Hill beneath Crawford Street, but under the impression that the residents evicted would be relocated, and new housing would be erected in the Lower Hill. This never occurred, and much of the demolished Lower Hill still remains as parking lots today (Rawson and Glasco 38-40).

This urban renewal project resulted in thousands of residents and hundreds of businesses being pushed out of the Hill. Along with urban redevelopment came racial disparities plaguing the city, neighborhoods becoming highly concentrated by ethnicity. “By 1960, Pittsburgh was one of the most segregated big cities in America” (old.post-gazette.com). Thus, the process of urban renewal staked its claim in Pittsburgh— an issue still haunting other neighborhoods to this very day. (If you want to read more about how urban renewal has effected other Pittsburgh areas over the years, read on here.)

“Combining the real and the imagined, things and thought on equal terms…these lived spaces of representation are thus the terrain for the generation of ‘counterspaces,’ spaces of resistance of the dominant order arising precisely from their subordinate, peripheral or marginalized positioning” - Edward Soja, Thirdspace: Journeys to Lost Angeles and Ither Real-and-Imagined Places

The 1960s was a time for resistance. Following the injustices that occurred in the Lower Hill, residents and leaders alike were ready to protect the Middle and Upper Hill from facing the same fate, as well as contest the racial discrimination happening throughout the city. In 1963, the United Negro Protest Committee (UNPC) rented a billboard at the corner of Crawford Street and Centre Avenue. The sign read: “NO Redevelopment Beyond This Point.” The intersection of Crawford St. and Centre Ave. became a starting point for many civil rights marches in the following years, a place known as Freedom Corner. It would later become a memorial commemorating the courageous activists that fought for social justice throughout the city.

The insurgence continued with civil rights demonstrations and local activism. Organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and women’s groups such as the YWCA organized marches to protest the inequalities in housing, education, and job opportunities (Rawson and Glasco 40-43).

“I was born to a time of fire.” - August Wilson, The Piano Lesson

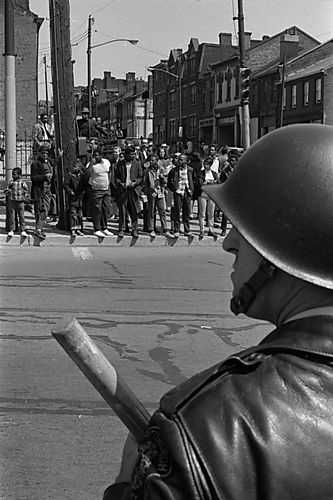

The civil rights demonstrations eventually went ablaze—literally. On April 4, 1968, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. Like in many other cities across the nation, riots broke out in some of Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods. The residents of the Hill felt the blows of injustice once again. In his activism for the Civil Rights Movement, MLK was a beacon of hope and inspiration for communities like the Hill District. The murder of this great man felt personal. People wanted to avenge Martin’s assassination. They wanted to scream until their voices were heard. They wanted to set the city on fire… and so, they did just that.

Amidst the chaos of the riots in the days following Dr. King’s death, fires were started in the business district of the Hill. About 500 fires destroyed much of the land that the community fought so hard to keep. After widespread destruction of houses and businesses in the Hill District, remaining vendors were forced to relocate to other neighborhoods in the city. The vibrant neighborhood declined, segregation worsened, and the people were left to “do for self” (Rawson and Glasco 47-49).

In the 1990s, the URA worked to reconcile the some of the violations made against the Lower Hill, even though the pain caused was irreversible. They funded the Crawford Square Apartments, mixed-income housing designed to draw more people back to the Hill. Since the 90s, the push for more mixed-income housing ensued, and more businesses and organizations have taken root in the Hill District. The neighborhood keeps thriving, accredited to the efforts of the residents who have kept their faith in the Hill (Rawson and Glasco 52).

Today, visitors can stop by Freedom Corner, located at the historical intersection of Crawford Street and Centre Avenue, to ponder all that took place in the Hill District. In 2001, sculptor Carlos Peterson and architect Howard Graves fashioned the memorial to honor the bravery of civil rights leaders and to remember how the Lower Hill was forever changed by urban renewal (Rawson and Glasco 62). Visitors can walk along the concrete rings to read the names of civil rights activists who chose peace over violence, or look upon the Spiritual Form that emulates the faith and courage of the community.

Accompanying the Spiritual Form are the words of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. made in his “I Have A Dream” speech. Guests should let his powerful message resonate with them as they remember all that the Hill has endured: “But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: in the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds.”

Works Cited

Fitzpatrick, Dan. "The Story of Urban Renewal." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

N.p., 21 May 2000. <http://old.postgazette.com/businessnews/20000521eastliberty1.asp>. Accessed 02 Mar. 2017.

Glasco, Laurence A., ed. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh PA, US: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004. ProQuest Febrary. Accessed 22 March 2017.

Glasco, Laurence A., and Christopher Rawson. August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays. Pittsburgh, PA: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2011. Print.

Soja, Edward. Thirdspace: Journeys to Lost Angeles and Ither Real-and Imagined Places. Cambridge MA: Blackwell Publishing Inc., 1996. 53-70.

Wilson, August. Fences. New York, NY: Plume, 1986. Print.

Wilson, August. The Piano Lesson. New York, NY: Plume, 1990. Print.